FILM REVIEW: "The Convert" is a historic odyssey with an important tale to tell

“This is the story of my life. So far.” is an explanation given for the traditional face-tattoo by those characters in The Convert who cross the cultural gap. In the same way, the very existence of this film marks our modern context as part of an exciting and important chapter where diverse and compelling representations of history can coexist on screen. The Convert wears its unique national identity on its sleeve, and while the White Saviour Complex seems to peek its head out in the first act, clichés dissolve as the film moves toward novel depths. Deeper questions, larger themes and broader messages are at play here.

Does it do a good enough job of representing Māori people and culture? As a White Australian dude, that judgment is not mine to pass. I can say, with certainty, that there is an apparent and authentic appreciation for the natural land of Epworth and surrounding islands. What I can also say, is that the Māori customs depicted feel intricate, framed with what seemed an appropriate reverence, yet do not distract, because they play so well into the context as necessary narrative devices.

I don’t doubt there was plenty of consultation with cultural representatives during production, and this allows The Convert to transcend the clichés to the point where its cross-cultural plot points feel earned. I think the use of subtitles only where necessary is a particularly strong choice, further enforcing the slow but not yet sure state of integration of the colonial into the traditionally owned culture.

Those deeper levels I’m talking about specifically arise as complex gravities of Prejudice, War and Peace. These three ideas, dissected in that order, are expertly married to one another through symbols and cool dialogue. Horses as bargaining chips, harbingers, or a link to natural innocence for example. There are lots of fun ideas both large and small to trace throughout the story. They’re all woven in a tapestry that speaks to more than what it reveals on the surface.

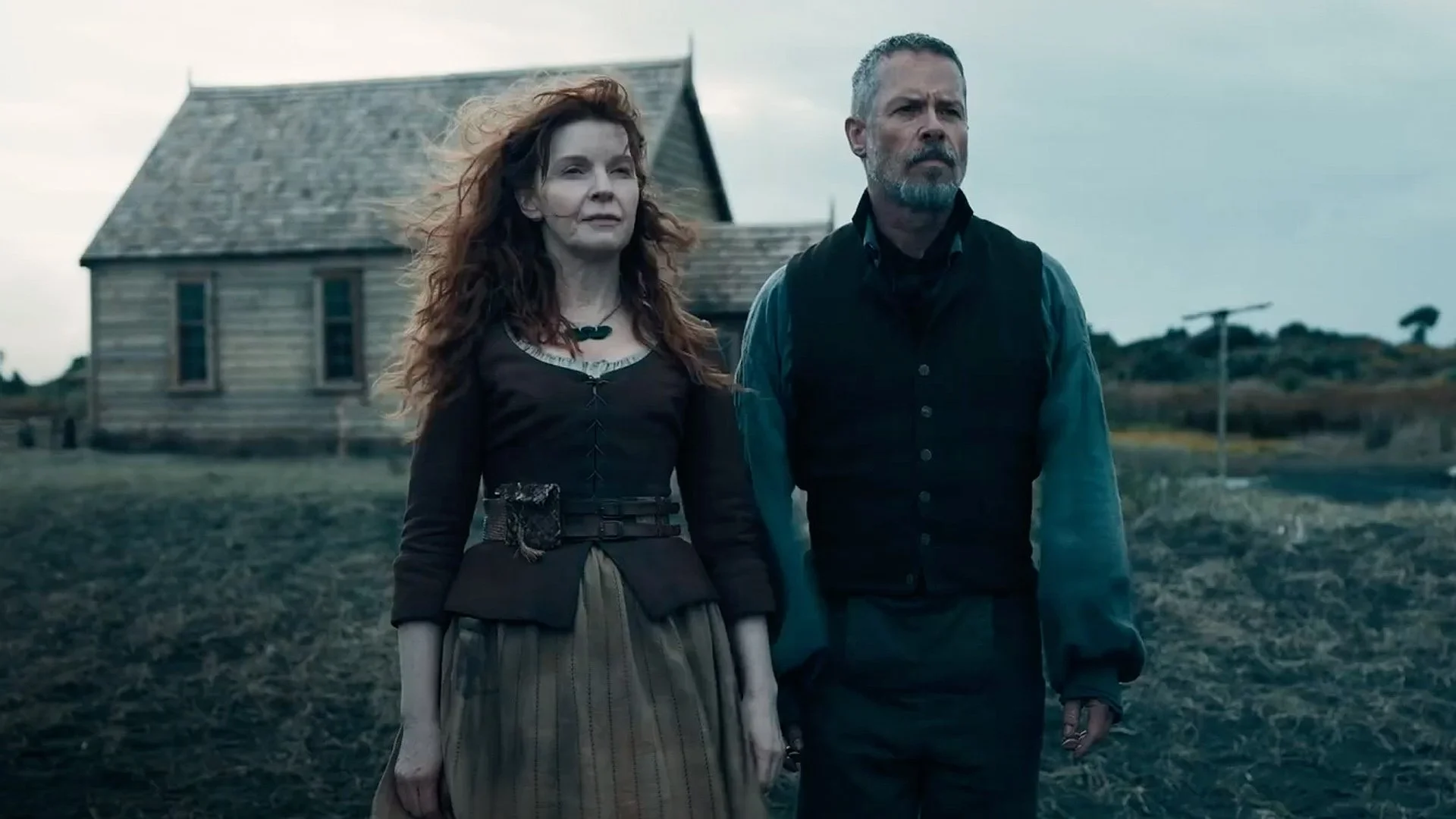

Beyond a few continuity errors, and a darker colour palate that at times makes important details (specifically during nocturnal scenes) nigh invisible, The Convert is extremely technically impressive. Sweeping drone shots of misty forest, the ferocious coastline and storms on the horizon continually gave me cause to pause.

If this idea strikes you as a little showy, be prepared for more of the same in The Convert, as it takes its liberty to bring out the best of what the NZ landscape has to offer. Special mention has to go to the dozen particularly strong shots which inhabit those key moments throughout the film where characters are in deep reconsideration of their choices and where they have yet to go. Subsequently, this is a film to watch only if you’re in the mood for an odyssey. While there are plenty of action scenes, they’re spaced out between the stretches of pensive thought and quiet world-building.

In conclusion, The Convert is a rich, symbolic portrait of an important moment of mutual understanding in the history of an enviously harmonious country.