Requiem for a film: Antoine Doinel De Francois Truffaut

France is the birth place of cinema. Starting out as a film critic, Truffaut was part of the nouvelle vague or new wave which attempted to revolutionise post-war cinema. The thing that differentiated him from other greats such as Godard, Bazin, Rohmer and Varda, was that Truffaut was never really interested in experimentation for its own sake. He was interested in creating strong narrative based films. Unsurprisingly, Truffaut managed to create 21 powerful feature length films which spawned a generation of innovative film making.

Five of his best loved films formed part of the Antoine Doinel series. The autobiographical series is centred on an enduring relationship between Truffaut and his cinematic counterpart Jean-Pierre Leaud. Laid over the course of twenty years, Doinel makes his first appearance as a cheeky 12 year old, eager to ward off trouble with a series of elaborate lies. The cinematography in 400 Blows created a precedent for the simplistic beauty which awarded him Best Director at Cannes. The film also featured one of the most copied devices in the history of the world-the film ending freeze frame and pan out of Antoine. Where is he going? What will become of him? Why am I reading into this? This has been endlessly copied, but never executed with such justification.

After the screening of the first instalment of the Antoine Doinel Series, Jean-Luc Godard famously posited the face of french cinema had changed.

“As soon as the screening was over, the lights came up in the tiny auditorium. There was silence for a few moments. Then Philippe Erlanger, representing the Quai d’Orsay, leaned over to André Malraux. “Is this film really to represent France at the Cannes festival?” “Certainly, certainly.” And so the minister for cultural affairs ratified the selection committee’s decision to send to Cannes, as France’s sole official entry, François Truffaut’s first full-length feature, The 400 Blows.

We cannot forgive you for never having filmed girls as we love them, boys as we see them every day, parents as we despise or admire them, children as they astonish us or leave us indifferent; in other words, things as they are. Today, victory is ours. It is our films that will go to Cannes to show that France is looking good, cinematographically speaking. Next year it will be the same again, you may be sure of that. Fifteen new, courageous, sincere, lucid, beautiful films will once again bar the way to conventional productions. For although we have won a battle, the war is not yet over.”

The narrative in the second instalment Antoine & Colette explores Dionel/Truffaut's fixation on chaos, cinema and love. It highlights the youth culture of the 1960s: the music, the conversations in cafes, the independence, the experiences Paris has to offer. Antoine is now 17, living in an apartment and working in a record factory and finds himself infatuated with Colette. She gives him subtle hints here and there but he fails to make a move. The film ends with him staying to watch TV with her parents while she goes out with her boyfriend.

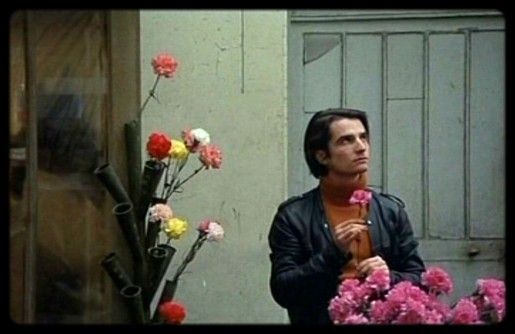

Truffaut maintains our interest in Stolen Kisses with a largely optimistic and upbeat tone. Antoine matures and deepens in Bed and Board with Truffaut granting Leaud increasing creative control in his character's development. Christine and Antoine are now happily married. We witness the couple's routine and conversations. Antoine is working as a florist and often experiments with dyes to create new carnations. Christine becomes pregnant and Antoine applies for a new job. He secures a new position at a hydraulics company and has an affair with a Japanese beauty named Kyoko.

The director is once again making a statement about Antoine's maturity and search for purpose. The balance between ambition and reality is as wide as ever- selling white carnations, yet dreaming to create the perfect red carnation. Subtle techniques like this appear throughout the series. For example, Antoine steals a kiss from Christine in her parent's wine cellar in Stolen Kisses, and she steals a kiss from him in the same setting in Bed and Board. Truffaut visually links the films by having Christine wear red on both occasions.

Love on the Run sees Antoine newly divorced from Christine. At the court he recognises Colette (a lawyer) in the distance. This film teaches us how life can be tragically beautiful. Leaud gets better with age too.

The way in which the director captures the city of Paris is beyond magnificent with its unique elements immediately recognisable. Truffaut's deep adoration for the city in which he lives is almost tangible: its architecture, boulevards, parks, cafes and cinemas are presented in an almost documentary format. Whilst other new wave directors carefully and pointedly curated film locations, Paris comes alive in Truffaut's work. The viewer falls in love with the beauty and squalor of every street corner of every arrondissement.

The Doinel series has taught me an incredible amount about creativity, purpose and life. From revolutionary criticism in the Cahiers du Cinema, to films which have advanced an unmatched cinematic legacy, Truffaut lived and breathed the things he loved. When it was time to change paths he did, without hesitation. Pursue things that are your raison d'etre. As an aside, I strongly recommend the Criterion Collection to anyone seeking an introduction to cinema sans HECS debt. It also provides for wonderful therapy.